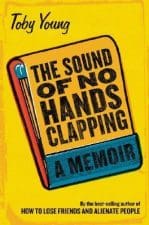

Meet Toby Young at mediabistro’s July 12 celebration and reading of The Sound of No Hands Clapping.

Meet Toby Young at mediabistro’s July 12 celebration and reading of The Sound of No Hands Clapping.

mediabistro: You’ve worked in multiple industries, including theater, journalism, books, and filmmaking. What’s the relative bridge-burning quotient in each? Which industry (or individuals within it) forgives quicker, which forgets, and which will never stop punishing you for prior offenses?

Also on Mediabistro

Toby Young: The general rule is that success absolves you of any sin. In my first

book, for instance, I was pretty heretical about Condé Nast, but I

got away with it because the book did quite well. Once it got onto

The New York Times‘ bestseller list, Si Newhouse had to call off his

assassins. If it had done badly, by contrast, I think I would have

disappeared without a trace. (This may be a total fantasy on my part.

It could be that Si is completely unaware of the book to this day.)

There is an exception to this rule: actors. Woe betide the writer who

dares to criticize an actor—and the better known the writer, the

more heinous the foul. For the past five years, I’ve been the drama

critic of the Spectator (Britain’s equivalent of The New Yorker) and

I don’t think a single actor I’ve given a bad notice to has forgiven

me. They have the memory of elephants.

This reminds me of an anecdote related by the Oscar-winning

screenwriter Frederic Raphael. It dates back to the 1970s when he was

writing plays for British television: “An actor came up to me and

asked whether I thought that the hydrogen bomb really represented a

threat to the future of the human race. I answered with a lot of on

the one hand, and then again on the other. I had given him, he said,

a lot to think about. Another actor sidled up to me and said, “May I

say something? When an actor asks whether you think that the human

race is threatened by atomic weapons, the required answer is, ‘I

think you’re giving an absolutely wonderful performance.'”

mediabistro: How do you follow up a success like your previous book? Was it

easier or harder to get started on The Sound of No Hands Clapping?

Young: Undoubtedly much harder. I knew that people would be gunning for me

after the success of the first book and that made me much more self-

critical. I’d write a chapter, read it back, and then screw it up

into a ball and hurl it across the room, saying, “It’s going to have

to be a lot better than that.”

In the end, after several deadlines had sailed past, I just decided

to get on with it. I realized there was no point in worrying what the

critics would say because they’ll all say the same thing: “I loved

the first one, but this one sucks.” And, of course, some of the

critics saying this will be the same ones who said that my first book

sucked five years ago.

mediabistro: Who/what friends or bigwigs have you alienated since your latest

book? How about those you pissed off around the time of the first

one—have any come back around?

Young: The Sound of No Hands Clapping was published in America on July 4 and

doesn’t come out in Britain until September 7, so it’s too early to

say. I’m hoping not to receive any threatening letters from high-

powered attorneys, which I did first time round. Having said that, I

did receive a call from Stephen Woolley, the guy who’s producing the

movie version of my first book and who appears as a character in the

latest one. He said he wasn’t particularly delighted with the way

I’ve portrayed him—and then added, as if the two things were

entirely unconnected, that he’s arranged to review it for The Times

of London.

mediabistro: What do you think about the “fake writer” controversies of late, for

example, James Frey and Kaavya Viswanathan?

Young: Well, those are two different controversies. In the case of James

Frey, he could have avoided all the trouble by including a simple

disclaimer at the beginning of A Thousand Little Pieces admitting

that he’d altered a few of the facts. It’s only because he tried to

pass off everything in his book as 100 percent true that he got busted.

I’ve

always made it very clear that only 95 percent of my books are true. It

probably helps that my memoirs are supposed to be funny. I think

readers grant authors a certain latitude if they make them laugh.

David Sedaris is a case in point. No one reading a book by him thinks

that every story he tells happened exactly the way he describes it.

They know he’s given things a little twist in order to make them

funny, in the same way you would if you were telling a story to a

group of friends in a bar.

Kaavya Viswanathan has been accused of plagiarism, which is a very

different charge. The thing that amazes me about cases like hers is

why the authors don’t bother to put what they’ve lifted from other

sources in their own words. I mean, even when I copied out large

chunks from text books in my school essays I knew enough to do that.

I do feel sorry for Kaavya Viswanathan, though. It’s terrible for a

writer’s career to be ended at such a young age. I hope she has

another go at writing a book, only this time all in her own words.

mediabistro: Where do your memoirs land on the authenticity spectrum? Is there

more pressure now to quantify how much you massaged actual events to

make them entertaining to readers? Did this come up between you and

your agent, editor or anyone else at Da Capo?

Young: I made it very clear to my editor at Da Capo, both in the case of How to Lose Friends and The Sound of No Hands Clapping, that I’ve given

some of the stories in both books a bit of top spin. He responded by

saying he wouldn’t have expected anything less and that, in fact,

he’d be very disappointed if I hadn’t made some things up. I’ve kept

a copy of that email because I have this terrible vision of some

diligent journalist going through both books with a fine-toothed comb

and teasing out all the fabrications. If that ever happens, at least

I’ll be able to prove that I never tried to hoodwink my editor.

mediabistro: What do you think of Oprah? Is she good for publishing?

Young: Yes, undoubtedly. I’m a huge fan—and I’m not just saying that

because I’d like to be on her show. What’s not to like about the fact

that she promotes books? The only people who object to it are snobs

who don’t like the idea of their own treasured little habits being

taken up by the hoi polloi. Literary culture is in decline and

anything that slows that process down is to be applauded.

mediabistro: What are you working on right now? What will your next book be

about? If you don’t know, what are you leaning towards?

Young: I’ve just co-authored a sex farce about the Royal Family that’s

debuting in an off-West End theatre on July 20. It’s the second play

I’ve written with Lloyd Evans, a fellow journalist whom I also share

the theatre beat with at the Spectator, and I hope we’ll write

several more. Plays don’t make any money—at least, ours don’t—but

it’s tremendously good fun writing them and putting them on. One of

the best things about playwriting is that the author is king. The

director literally can’t change a word without the writer’s consent.

That’s very different from the movie business, obviously, and that’s

one of the reasons successful screenwriters are so well paid—it’s a

way of compensating them for being so incredibly disrespected. As one

screenwriter said about working for the Hollywood studios: “They ruin

your stories. They trample on your pride. They massacre your ideas.

And what do you get for it? A fortune.”

mediabistro: What is the state of book publishing—best and worst thing about the

industry right now?

Young: It’s a winner-take-all economy. If you’re in the winner’s enclosure,

that’s great, obviously, but if you’re not, it’s terrible. The number

of authors who actually make a living from book-writing in the United

States—and I’m talking about proper books, rather than text books—

is less than 200. As a career choice, writing books is about as

rational as playing the New York Lottery. Still, there are

compensations. You get to describe yourself as a “published author”

at parties and prestigious Web sites solicit your opinions about stuff.

|

“I write down

|

mediabistro: How long can you make a living going places, then being cast out?

At a

certain point, will you have to live in a cave?

Young: I think I have one more memoir in me, then I’m going to wait 25

years, and start publishing my diaries. Otherwise, as you say, I’d

have to live in a cave. The great thing about the diary form is that

you really can burn all your bridges there because you’re so close to

death by the time they’re published that you’ve got nothing to lose.

I started keeping a diary four years ago and I think I’ve already

accumulated enough material for at least one volume. I write down

every juicy piece of gossip I hear, particularly about celebrities. I

can’t publish any of it now because of the libel laws—it’s all

rumor and hearsay, obviously—but if I wait for the subjects to

shuffle off their mortal coils, I’ll be fine. You can’t libel the

dead. Or, rather, you can, but they can’t sue you for it. As Mae West

said, “Keep a diary and some day it’ll keep you.”

mediabistro: The current obsession with celebrities was just picking up steam

when

you came to New York as a journalist in the mid-90’s- does the fact that

popular culture is fixated on celebs these days make your life/job any

easier, considering your area of expertise (pissing off big names, then

documenting it)?

Young: I’m interested in celebrities as a collective group but I can’t

muster much interest in individual celebrities any more. They all

tend to blend into one another. Like most other journalists, I’m

waiting with bated breath for the public to turn on the celebrity

class, but every time you think people’s interest in them must have

peaked, it then increases exponentially. Indeed, I think it might even

be possible to come up with a similar rule to the one about

microprocessor speed: the number of column inches about celebrities

in the national press doubles every 18 months. One of my long-term

projects is a novel called Starmaggedon about a dystopian future in

which celebrities have become the underclass. Realistically, though,

I don’t think that’s going to happen for a very long time.

mediabistro: With the focus on family life in your latest book, and the

associated revelations, some might accuse you of going soft. Share

a recent story/anecdote to the contrary.

Young: One story that isn’t in the book is that a day after my first child

was born I waited for my wife and baby to fall asleep and then crept

out of the house and went to a party. Unfortunately, for the rest of

the evening I kept bumping into my wife’s friends, all of whom asked

what on earth I was doing out drinking given that Caroline had had a

baby 24 hours earlier. I managed to sneak back into the house without

waking up my wife, but the following day all her friends called her

to tell her they’d seen me out the night before. My marriage still

hasn’t recovered from that.

**

Rebecca L. Fox is mediabistro’s features editor.

Topics:

Interviews

.png)